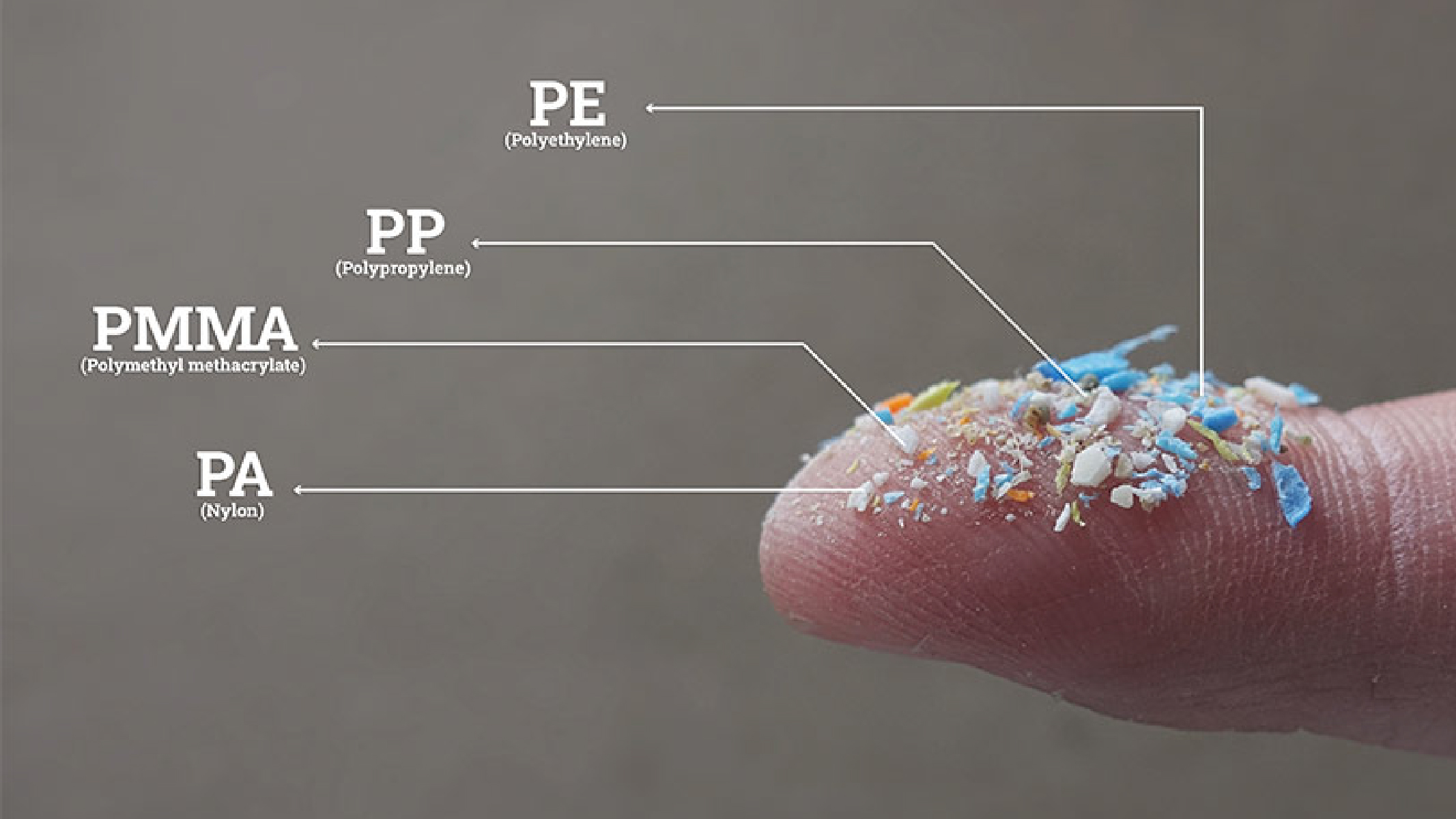

Once in the environment, microplastics do not biodegrade. They accumulate in animals, including fish and shellfish, and are consequently also consumed as food by humans.

Microplastics have been found in marine, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems as well as in food and drinking water. Their continued release contributes to permanent pollution of our ecosystems and food chains. Exposure to microplastics in laboratory studies has been linked to a range of negative (eco)toxic and physical effects on living organisms.

Prompted by concerns for the environment and on people’s health, several EU Member States have already enacted or proposed national bans on intentional uses of microplastics in consumer products. The bans concern mainly uses of microbeads in cosmetics that are rinsed off after use, where the microplastics are used as abrasive and polishing agents.

Each year around 42 000 tonnes of microplastics end up in the environment when products containing them are used. The largest single source of pollution is the granular infill material used on artificial turf pitches, with releases of up to 16 000 tonnes. In addition, the releases of unintentionally formed microplastics (when larger pieces of plastic wear and tear) are estimated to be around 176 000 tonnes a year to the European surface waters.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has in 2016 reviewed the available evidence on micro- and nanoplastics in food in 2016. Experts identified the need to generate more data on their occurrence levels in food and on their potential effects on human health. To that end, EFSA is holding a scientific colloquium in 2021 to discuss the current state of play and ongoing research in this field.

Microplastics are intentionally added to a range of products including fertilisers, plant protection products, cosmetics, household and industrial detergents, cleaning products, paints and products used in the oil and gas industry. Microplastics are also used as the soft infill material on artificial turf sports pitches.

In consumer products, microplastic particles are best known for being abrasives (e.g. as exfoliating and polishing agents in cosmetics known as microbeads), but they can also have other functions, such as controlling the thickness, appearance and stability of a product. They are even used as glitters or in make-up.

Overall, around 145 000 tonnes of microplastics are estimated to be used in the EU/EEA each year.

In 2017, the European Commission requested ECHA to assess the scientific evidence for taking regulatory action at the EU level on microplastics that are intentionally added to products (i.e. substances and mixtures).

In January 2019, ECHA proposed a wide-ranging restriction on microplastics in products placed on the EU/EEA market to avoid or reduce their release to the environment. A consultation on the restriction proposal was organised from March to September 2019. ECHA received 477 individual comments. Details of the consultation, including non-confidential responses, are available on ECHA’s website.

The proposal is expected to prevent the release of 500 000 tonnes of microplastics over 20 years.

Other options for reducing the releases of unintentionally formed microplastics in the aquatic environment are being considered by the Commission as part of its Plastics Strategy and the new circular economy action plan.

ECHA’s Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC) adopted its opinion in June 2020. It supported the proposal while recommending more stringent criteria for derogating biodegradable polymers as well a ban after a transition period of six years for microplastics used as infill material on artificial turf pitches. RAC also concluded that the lower limit size of 100 nanometres (nm) for restricting microplastics as proposed by ECHA is not necessary for enforcement and recommended no lower limit size.

The Committee for Socio-economic Analysis (SEAC) adopted its opinion in December 2020. It supported ECHA’s proposal but made some recommendations for the European Commission to consider in the decision-making phase.

SEAC recommended, among other things, a lower size limit of 1 nm for restricting microplastics. It also considered that a temporary lower size limit of 100 nm may be necessary to ensure that the restriction can be enforced by detecting microplastics in products.

To control the release to the environment of infill material from artificial turf pitches, SEAC did not prefer any of the risk management options proposed by ECHA over the others. The committee stated that the eventual choice would depend on policy priorities, specifically regarding the reduction of emissions.

The Commission adopted the restriction on 25 September 2023. The first measures, for example the ban on loose glitter and microbeads, start applying on 17 October, when the restriction enters into force. In other cases, the sales ban will apply after a longer period to give affected stakeholders the time to develop and switch to alternatives.