Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large class of thousands of synthetic chemicals that are used throughout society. However, they are increasingly detected as environmental pollutants and some are linked to negative effects on human health.

They all contain carbon-fluorine bonds, which are one of the strongest chemical bonds in organic chemistry. This means that they resist degradation when used and also in the environment. Most PFAS are also easily transported in the environment covering long distances away from the source of their release.

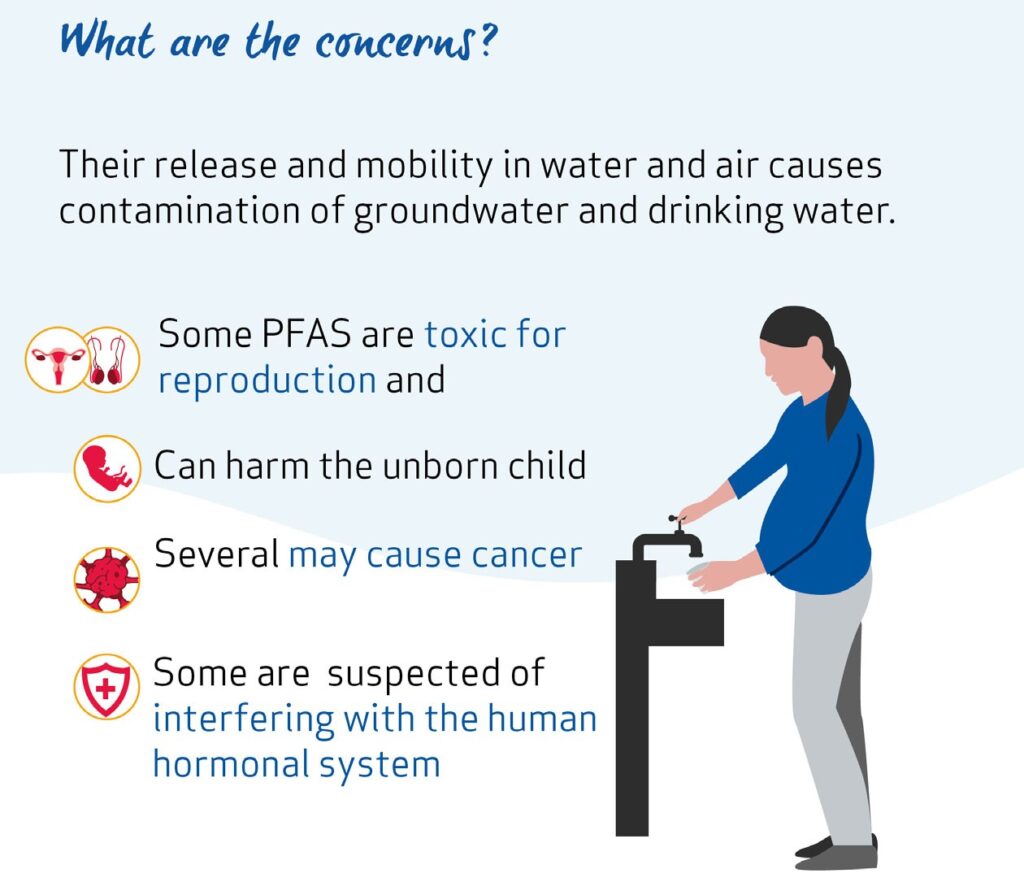

PFAS have been frequently observed to contaminate groundwater, surface water and soil. Cleaning up polluted sites is technically difficult and costly. If releases continue, they will continue to accumulate in the environment, drinking water and food.

PFAS have a wide range of different physical and chemical properties. They can be gases, liquids, or solid high-molecular weight polymers. Some PFAS are described as long-chain or short-chain, but this does not cover all of the different kinds of structures that are present in the PFAS class, which is very diverse. PFASs can be sorted in many ways based on their structure.

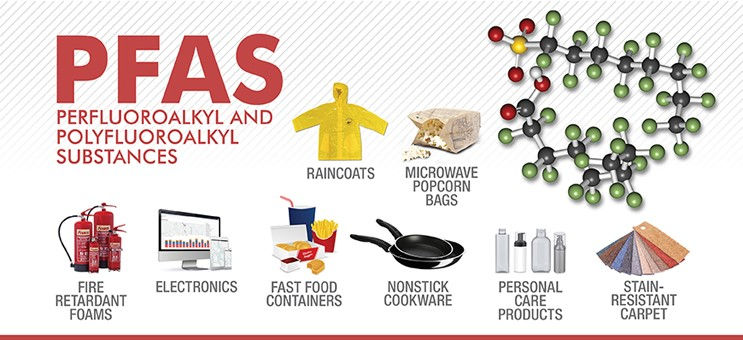

PFAS are widely used as they have unique desirable properties. For instance, they are stable under intense heat. Many of them are also surfactants and are used, for example, as water and grease repellents.

Some of the major industry sectors using PFAS include aerospace and defence, automotive, aviation, food contact materials, textiles, leather and apparel, construction and household products, electronics, firefighting, food processing, and medical articles.

Over the past decades, global manufacturers have started to replace certain PFAS with other PFAS or with fluorine-free substances. This trend has been driven by the fact that scientists and governments around the world first recognised the harmful effects of some PFAS (particularly long-chain PFAS) on human health and the environment. As the focus shifted to other PFAS, these have also been found to have properties of concern.

The majority of PFAS are persistent in the environment. Some PFAS are known to persist in the environment longer than any other synthetic substance. As a consequence of this persistence, as long as PFAS continue to be released to the environment, humans and other species will be exposed to ever greater concentrations. Even if all releases of PFAS would cease tomorrow, they would continue to be present in the environment, and humans, for generations to come.

The behaviour of PFAS in the environment means that they tend to pollute groundwater and drinking water, which is difficult and costly to remediate. Certain PFAS are known to accumulate in people, animals and plants and cause toxic effects. Certain PFAS are toxic for reproduction and can harm the development of foetuses. Several PFAS may cause cancer in humans. Some PFAS are also suspected of interfering with the human endocrine (hormonal) system.

PFAS are released into the environment from direct and indirect sources, for example, from professional and industrial facilities using PFAS, during use of consumer products (e.g. cosmetics, ski waxes, clothing) and from food contact materials. Humans can be exposed to them every day at home, in their workplace and through the environment, for example, from the food they eat and drinking water.

In June 2022, the Stockholm Convention parties decided to include PFHxS, its salts and related compounds in the treaty. The Commission added the substance group in the EU’s POPs Regulation in May 2023 and the regulation entered into force on 28 August 2023.

Long-chain perfluorinated carboxylic acids (C9-21 PFCAs) are being considered for inclusion in the Stockholm Convention and consequent global elimination.

The national authorities of Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden are proposing a restriction covering a wide range of PFAS uses – in support of the statements made in the Environment Council in December 2019. They submitted their proposal to ECHA in January 2023, and ECHA’s scientific committees are now evaluating it.

Furthermore, ECHA introduced in January 2022 a restriction proposal for PFAS used in firefighting foams. ECHA’s scientific committees supported the proposal in their opinions finalised in June 2023. The European Commission together with the EU countries will decide on the restriction in due course. This use is not included in the universal PFAS restriction proposed by the five national authorities.

- 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2-(heptafluoropropoxy)propionic acid, its salts and its acyl halides (HFPO-DA), a short-chain PFAS substitute for PFOA in fluoropolymer production, was the first substance added to the Candidate List. Its ammonium salt is commonly known as GenX. [General Court judgment];

- perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) and its salts, a replacement of PFOS; and

- perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA) and its salts.

Several additional PFAS are on the list for evaluation (Community rolling action plan) over the coming years or have already been evaluated. The evaluation aims to clarify initial concerns on the potential risk to human health or the environment that manufacturing or using these substances could pose.

- perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA);

- ammonium pentadecafluorooctanoate (APFO);

- perfluorononan-1-oic acid (PFNA) and its sodium and ammonium salts;

- nonadecafluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) and its sodium and ammonium salts; and

- perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA).

The recast of the Drinking Water Directive, which took effect on 12 January 2021, includes a limit of 0.5 µg/l for all PFAS. This is in line with a grouping approach for all PFAS.